MIND (SNF Eccellenza)

The project MIND was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation as a Eccellenza Fellowship (Grant No. PCEFP2_181115) and ran from Sep. 2019 - Aug. 2024. This page gives an overview of its outcomes. Work was conducted under three Objectives, described below.

Lay summary

The MIND research project investigated how carbon and nitrogen circulate in ecosystems, how water and carbon cycles are linked, and how forests respond to climate change. A key objective was to link the theory of eco-evolutionary optimality with various observations. To this end, we developed a new version of an ecosystem model that describes how plants adapt to their environment and how these adaptations affect the entire ecosystem. This model was then used to assimilate various observations, enabling more accurate and realistic simulations. In general, it was shown that observed changes in the structure and functioning of ecosystems are explainable and predictable, and that vegetation responds dynamically to changing environmental conditions. By combining theory, data, and modeling, MIND provides new insights into the behavior of terrestrial ecosystems. The results help to better predict how forests and other vegetation will respond to current and future climate change and how stable natural carbon and nutrient cycles will remain.

Objective A: Nutrient controls on C cycling

Under this objective, we compiled empirical data from diverse types of observations to quantify global rates of N cycling and to evaluate a next-generation ecosystem C-N model, informed by eco-evolutionary optimality principles.

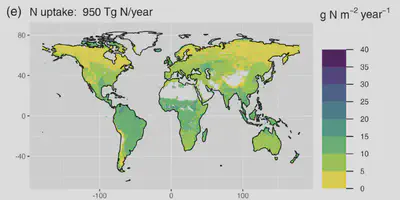

Work started by generating an estimate of the annual rate of total plant nitrogen (N) uptake and its global distribution—a key variable for improving our quantitative understanding of the N cycle. Previous estimates made incomplete use of available published data. Our re-attempt to quntify total global N uptake therefore provided a suitable starting point for the PhD student as it required us to compile published data on a set of related variables (terrestrial ecosystem net primary productivity, separated by plant compartments; C:N stoichiometry of different plant compartments, N resorption, net soil N mineralisation rates). This dataset was published separately (Peng and Stocker, Benjamin, 2024). Our estimate (950 ± 260 Tg N year−1) for the total global N uptake is at the upper range of estimates based on model simulations (Peng et al., 2023). We also investigated the controls on global variations in N uptake and found that the relative allocation of biomass production in different tissues was a particularly important process driving variations in vegetation N uptake. The data compilation that on constituent variablels

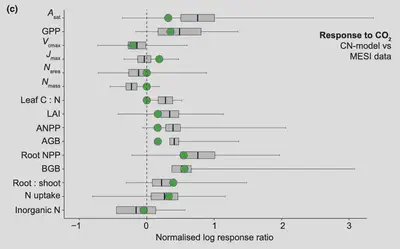

Next, we targeted observations from ecosystem manipulation experiments and investigated how growth, allocation, C:N stoichiometry and photosynthesis respond to altered N inputs and elevated CO2. Also here, we started by gathering published data from empirical work. To avoid duplication of efforts, we tightly coordinated work with collaborators and contributed to a publication of the MESI dataset—a comprehensive data compilation from ecosystem manipulation experiments, suitable for meta-analysis and model-data integration (Van Sundert et al., 2023). This dataset was published separately (Van Sundert et al., 2023). We then proceeded to analysing results from CO2 experiments with a focus on the coordination of responses in leaf photosynthesis and biomass. Our findings support neither control of leaf photosynthetic capacity (measured by Vcmax) by N supply, nor the N dilution hypothesis which posits that declines of leaf N content under elevated CO2 are due to accelerated biomass production. They are however consistent with reduced leaf-level N demand in response to elevated CO2 (Peng et al., in prep.).

The results from this empirical analysis and the published perspectives paper on general principles and theoretical approaches for vegetation modelling by (Franklin et al., 2020) guided the further development of a model for predicting the coupled carbon (C) and N cycling in terrestrial ecosystems based on eco-evolutionary optimality theory. The model, referred to as ‘CN-model’ (Stocker and Prentice, 2024), constitutes a major output of this project. It provides a blueprint for translating the functional balance hypothesis—which posits that the balance of leaf vs. fine root growth is coordinated such that C assimilation and N acquisition are in the right balance for satisfying stoichiometric requirements—into a dynamic model of ecosystem C and N cycling, scalable for global-scale applications. Model code is currently available on Github (https://github.com/stineb/rsofun/releases/tag/v1.0_cnmodel) and will be published on Zenodo upon publication of a peer-reviewed article. Insights gained from the empirical and theoretical work on coupled C and N cycling also provided a basis for reviewing the current state of global C-N models, their simulation of terrestrial C sink trends and how observed patterns can be translated into model implementations guided by eco-evolutionary optimality (Stocker et al., 2025b) (see figure below) and observed responses (grey bars) to increased CO2, based on MESI data (Van Sundert et al., 2023). Modelled response ratios are based on the CN-model. Figure from Stocker et al., (2025).). The following general insights from this review are particularly important in the context of the project MIND: First, we found strong support for a shift in above vs. belowground allocation upon N fertilisation and elevated CO2. Second, soil N availability has no influence on photosynthetic capacity (measured by Vcmax). Third, the atmospheric environment (temperature, humidity, CO2) influences leaf photosynthetic traits. Fourth, these general patterns found in the data are predictable from eco-evolutionary optimality principles and are accurately simulated by the CN-model (see figure below) and observed responses (grey bars) to increased CO2, based on MESI data (Van Sundert et al., 2023). Modelled response ratios are based on the CN-model. Figure from Stocker et al., (2025).).

The work under the Objective Nutrient Controls on C cycling also provided synergies with other ongoing work in my group. The data from (Stocker and Tian, 2024b) were used for Peng et al., 2023, while related work on determining environmental vs. phylogenetic controls on leaf N, P, and N:P was carried out and published (Stocker and Tian, 2024a; Tian et al., 2024). Insights gained from the work on model-data comparisons and integration on the basis of ecosystem experimental data also provided material for the review by (Caldararu et al., 2023). The work on nutrient-carbon cycle relations informed contributions to several other publications to which MIND project members made contributions as co-authors (Joos et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2021; Sophia et al., 2024).

Objective B: Water limitation in a changing climate

Under this objective, we investigated how vegetation sensitivity to droughts, its variations across space globally, its relations to rooting depth and topography and how to use eco-evolutionary optimality principles for accurate predictions of plant functioning under water stress.

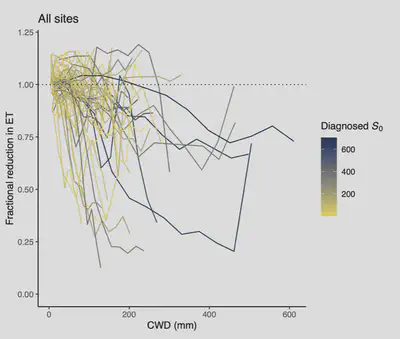

Work started with a focus on quantifying plant-available water storage and characterising water-vegetation activity relations using two different data types—ecosystem fluxes from eddy-covariance measurements for site-scale analyses and satellite remote sensing data for global scale analyses. For the site-scale analyses, we estimated the relative reduction in evapotranspiration due to root-zone moisture limitation. The approach taken relied on modelling a potential evapotranspiration rate using a deep neural network, trained on a moist-conditions subset of the data for each site, and contrasing it to actual evapotrantranspiration rates (code is made open access (Giardina, 2023)). This approach provided a new angle at detecting subsurface conditions (in this case water limitation) from aboveground measurements—available from a large number of globally distributed sites. Our results revealed a large variation in water stress relations across sites. While evapotranspiration rates were sustained at nearly their estimated potential rates despite long-lasting rain-free periods at some sites, evapotranspiration rapidly declined with increasing dryness at other sites (Giardina et al., 2023). These large variations could only partially be explained by commonly available site characteristics (vegetation type, soil conditions estimated from global soil maps, etc.). Our interpretation is that unknown subsurface structure (soil depth, groundwater table depth, bedrock porosity, etc.) is a major determinant explaining large variations of water stress relations across sites. This is an important result, indicating a major inherent limitation for modelling ecosystem fluxes across space—the modelling task addressed by Land Surface Models.

A complementary approach to quantifying water stress relations made use of satellite Earth Observation data. Instead of locally measured evapotranspiration, we used a data product based thermal remote sensing, which proved to yield reliable estimates also under dry conditions. The global analysis, performed at 0.05° (~5 km around the Equator) yielded insights that are consistent with the findings from (Giardina et al., 2023), showing a large variation of the (plant-available) rooting zone water storage across small spatial scales (Stocker et al., 2023). Hence, variations of vegetation sensitivity to dry conditions arise not only across large climatic gradients and biomes, but also across smaller-scale topographic gradients. Again, we interpreted this as a reflection of the subsurface structure and hydrology and of the rooting depth of plants.

Thanks to the global scale of the analysis, our map of the rooting-zone water-storage capacity—made available open access (Stocker, 2024b)—provides much needed information for specifying respective information in Land Surface Models, or for benchmarking state-of-the-art models as done in (Giardina et al., 2025). The work leading up to the publication of the global analysis by (Stocker et al., 2023) in Nature Geoscience spurred the development of a solution for efficient handling of big Earth Observation data for computationally demanding time series-based modelling. The respective code was published as an R package (Bernhard et al., 2025) and facilitated work for other projects (Helpap et al., 2025). Also the algorithm for calculating cumulative water deficit timeseries (from with the rooting-zone water-storage capacity is derived) has been implemented as an R package and has been re-used for other studies (Helpap et al., 2025), supervised Bachelor and Master theses, and teaching material (Stocker, 2024a).

On the empirical basis developed in (Giardina et al., 2023) and (Stocker et al., 2023, the simulation of water stress relations for modelling water and carbon fluxes was advanced in several studies. In Joshi et al. (2022), we developed a reduced-form representation of plant hydraulic relations and stomatal optimisation. Our theoretical approach was shown to accurately predict responses in several variables to soil dry-downs and is being further developed for simulating ecosystem carbon and water fluxes (Joshi et al., in prep.). The work on water-carbon cycle relations and drought impact detection and prediction informed contributions to several other publications to which MIND project members made contributions as co-authors (Kladny et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2022).

Objective C: Scaling from trees to the forest

Under this objective, we investigated how forest dynamics interact with tree growth and how previously untapped data resources can be used to achieve a data-informed simulations of forest dynamics in response to a chaning environment.

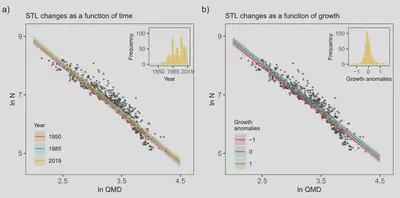

We started by gathering data from unmanaged forests in Switzerland to quantify changes in the self-thinning relationship—addressing the question of whether forests are thickening. The self-thinning relationship describes how the number of trees in a forest stand declines as the average size of trees in that stand increases over the course of stand development and maturation. The data we gathered clearly reflects this relationship. There is an upper “edge” beyond which mutual shading and competition for other resources (water, nutrients) prevents forest from developing into even thicker stands. Our hypothesis was that environmental change alters resource limitations, e.g., through an warming-related extension of the growing season, rising CO2 and its effect on photosynthesis, and altered nutrient inputs from atmospheric deposition. The analysis of long-term forest trends is complicated by the fact that in many regions of the globe, including Switzerland, forest stand dynamics today (at leas partly) reflect the forest use of the past and that these legacy effects play out over multiple decades to even centuries. It is therefore challenging to disentangle drivers of forest change—a chaning environment or recovery from past forest use? Our approach to avoid this complication was to analyse self-thinning trends. They would reflect a change in the “carrying capacity” of a forest stand, after recovery from past forest use, and at a point where dynamics are dominated by (natural) self-thinning process. We thereby achieve an effective separation of recovery from past disturbance vs. shifting maximum carrying capacity. The focus on forests in Switzerland provided a suitable starting point in view of the high-quality forest data from repeated sampling, with oldest data from the 1930s.

We found a general shift in the self-thinning relationship, pointing to a trend of relieved self-thinning constraints and higher forest carrying capacities (Marqués et al., 2023b) We also found a clear relationship between the self-thinning line and forest stand growth. More vigurously growing stands exhibit a higher carrying capacity, growing into thicker stands.

The empirical forest data analysis was complemented by model simulations. For this, we adopted the BiomeE model and implemented it within our general modelling framework rsofun (Stocker et al., 2025a). This clarifyied our mechanistic interpretation of observed patterns in the data. The model also simulated an upward shift of the self-thinning relationship (line in figure above) and a positive relationship between growth and biomass changes. However, there is a distinct non-linearity in this relationship, leading to muted changes in biomass stocks (smaller relative enhancement of steady-state biomass stocks than of biomass growth). The degree of this non-linearity is strongly controlled by model assumptions and parameter choices. This work generated two important findings: First, faster tree growth can be expected to drive a sustained C sink in thickening forests despite an acceleration of forest stand dynamics and biomass turnover. Second, the simulation of these dynamics critically depends on poorly constrained model parameters. Our analysis of Swiss forests also sparked several additional works. The non-linearity of relationships between C fluxes and C stocks appeared from our analysis as a key metric describing the (modelled) dynamics of the terrestrial C cycle. This motivated the analysis of linearity of modelled relationships between photosynthesis, growth, and C storage in different plant compartments from outputs of global C cycle models (Zhang-Zheng et al., 2025). The analysis of (Marqués et al., 2023b) revealed a pattern that could influence the global carbon cycle and the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere, if the changes in self-thinning and forest carrying capacity appear generally across forests globally. Therefore, we have gathered data from forests globally and analysed self-thinning trends and quantified respective consequences for the terrestrial C sink (Marqués et al., in prep.).

Towards a next-generation vegetation modelling framework

A unifying aim of the different work strands pursued in the project was to integrate developments into a novel modelling framework. Work was therefore designed to yield new benchmarks and model calibration targets that are systematically being used for extending the model-data integration and all model applications and developments were designed to yield re-usable outputs in the form of successive developments of the open access modelling framework rsofun — now integrating the eco-evolutionary optimality-based photosynthesis model (P-model, Stocker et al. (2020)) and the forest dynamics model (BiomeE), used in (Marqués et al., 2023b). We further developed the code to enable the use of the P-model within BiomeE (yielding ‘BiomeEP’). This constitutes substantial novelty and enabled us to participate in a larger model intercomparison project for vegetation demography models (Eckes‐Shephard et al., 2025). The rsofun modelling framework is implemented as an R package and is available on the curated central library repository for R packages (CRAN). To mark the release of this package and provide a description of its implementation of model-data integration, we published an article (Paredes et al., 2025, a revised version of this article has been accepted for publication after peer review in Geoscientific Model Development on 11.11.2025).

Several other works that were carried out over the course of the project MIND further contributed to advancing rsofun as a central modelling framework that integrates multiple strands of related research. (Schneider et al., 2025) demonstrated that the P-model accurately simulates the acclimation and adaptation of the photosyntheis thermal optimum. (Luo et al., 2023) revealed a systematic reduction of spring photosynthesis rates from ecosystem flux measurements at differen sites and showd how the effect can be represented in photosynthesis models to yield more accurate simulations of springtime CO2 assimilation of vegetation in winter-cold climates.

We also addressed a fundamental question regarding the relation of phenology and photosynthesis that directly relates to assumptions underlying many carbon cycle models, including modelling work in this project. Responding to recently published results and using the P-model in our modelling framework rsofun, we showed that autumn leaf phenology (senescence) is delayed or stable despite a general trend of earlier leaf-unfolding in spring and despite higher photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in the early season (Marqués et al., 2023a).

Outputs

Pre-prints and submitted articles

2025

• Helpap, P., Brönnimann, S., Hand, R., Franke, J., and Stocker, B. D.: Are modern droughts unprecedented?, https://doi.org/10.22541/essoar, 2025.

• Zhang-Zheng, H., Arora, V. K., Anthoni, P., Pugh, T. A. M., Jain, A. K., Yuan, W., Malhi, Y., Nabel, J., Goll, D. S., Pongratz, J., Poulter, B., Walker, A. P., Zaehle, S., Knauer, J., Kato, E., Ding, R., Tang, M., Sitch, S., O’Sullivan, M., Terrer, C., Tian, H., Pan, N., Friedlingstein, P., Ito, A., Sun, Q., Decayeux, J., and Stocker, B. D.: Diagnosing linearity along the carbon cascade in terrestrial biosphere models, bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.09.01.673458, 2025

2024 Stocker, B. D. and Prentice, I. C.: CN-model: A dynamic model for the coupled carbon and nitrogen cycles in terrestrial ecosystems, https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.25.591063, bioRxiv, 2024.

• Paredes, J. A., Hufkens, K., Marcadella, M., Bernhard, F., and Stocker, B. D.: rsofun v5.0: A model-data integration framework for simulating ecosystem processes, bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.24.568574, 2025.

Published peer-reviewed articles

2025

• Eckes-Shephard, A. H., Argles, A. P. K., Brzeziecki, B., Cox, P. M., De Kauwe, M. G., Esquivel-Muelbert, A., Fisher, R. A., Hurtt, G. C., Knauer, J., Koven, C. D., Lehtonen, A., Luyssaert, S., Marqués, L., Ma, L., Marie, G., Moore, J. R., Needham, J. F., Olin, S., Peltoniemi, M., Piltz, K., Sato, H., Sitch, S., Stocker, B. D., Weng, E., Zuleta, D., and Pugh, T. A. M.: Demography, dynamics and data: building confidence for simulating changes in the world’s forests, New Phytologist, p. nph.70643, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.70643, 2025.

• Schneider, P. D., Gessler, A., and Stocker, B. D.: Global Photosynthesis Acclimates to Rising Temperatures Through Predictable Changes in Photosynthetic Capacities, Enzyme Kinetics, and Stomatal Sensitivity, Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 17, e2024MS004 789, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024MS004789, 2025.

• Stocker, B. D., Dong, N., Perkowski, E. A., Schneider, P. D., Xu, H., de Boer, H. J., Rebel, K. T., Smith, N. G., Van Sundert, K., Wang, H., Jones, S. E., Prentice, I. C., and Harrison, S. P.: Empirical evidence and theoretical understanding of ecosystem carbon and nitrogen cycle interactions, New Phytologist, 245, 49–68, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.20178, 2025.

2024

• Liu, J., Ryu, Y., Luo, X., Dechant, B., Stocker, B. D., Keenan, T. F., Gentine, P., Li, X., Li, B., Harrison, S. P., and Prentice, I. C.: Evidence for widespread thermal acclimation of canopy photosynthesis, Nature Plants, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01846-1, 2024.

• Sophia, G., Caldararu, S., Stocker, B. D., and Zaehle, S.: Leaf habit drives leaf nutrient resorption globally alongside nutrient availability and climate, Biogeosciences, 21, 4169–4193, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-21-4169-2024, 2024.

• Tian, D., Yan, Z., Schmid, B., Kattge, J., Fang, J., and Stocker, B. D.: Environmental versus phylogenetic controls on leaf nitrogen and phosphorous concentrations in vascular plants, Nature Communications, 15, 5346, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49665-4, 2024.

• Kladny, K.-R., Milanta, M., Mraz, O., Hufkens, K., and Stocker, B. D.: Enhanced prediction of vegetation responses to extreme drought using deep learning and Earth observation data, Ecological Informatics, 80, 102 474, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102474, 2024.

2023

• Keenan, T. F., Luo, X., Stocker, B. D., De Kauwe, M. G., Medlyn, B. E., Prentice, I. C., Smith, N. G., Terrer, C., Wang, H., Zhang, Y., and Zhou, S.: A constraint on historic growth in global photosynthesis due to rising CO2, Nature Climate Change, pp. 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01867-2, 2023

• Marqués, L., Weng, E., Bugmann, H., Forrester, D. I., Rohner, B., Hobi, M. L., Trotsiuk, V., and Stocker, B. D.: Tree Growth Enhancement Drives a Persistent Biomass Gain in Unmanaged Temperate Forests, AGU Advances, 4, e2022AV000 859, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022AV000859, 2023

• Peng, Y., Prentice, I. C., Bloomfield, K. J., Campioli, M., Guo, Z., Sun, Y., Tian, D., Wang, X., Vicca, S., and Stocker, B. D.: Global terrestrial nitrogen uptake and nitrogen use efficiency, Journal of Ecology, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.14208, 2023

• Luo, Y., Gessler, A., D’Odorico, P., Hufkens, K., and Stocker, B. D.: Quantifying effects of cold acclimation and delayed springtime photosynthesis resumption in northern ecosystems, New Phytologist, 240, 984–1002, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19208, 2023.

• Giardina, F., Gentine, P., Konings, A. G., Seneviratne, S. I., and Stocker, B. D.: Diagnosing evapotranspiration responses to water deficit across biomes using deep learning, New Phytologist, 240, 968–983, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19197, 2023

• Caldararu, S., Rolo, V., Stocker, B. D., Gimeno, T. E., and Nair, R.: Ideas and perspectives: Beyond model evaluation – combining experiments and models to advance terrestrial ecosystem science, Biogeosciences, 20, 3637– 3649, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-3637-2023, 2023

• Stocker, B. D., Tumber-Dávila, S. J., Konings, A. G., Anderson, M. C., Hain, C., and Jackson, R. B.: Global patterns of water storage in the rooting zones of vegetation, Nature Geoscience, pp. 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01125-2, 2023.

• Van Sundert, K., Leuzinger, S., Bader, M. K.-F., Chang, S. X., De Kauwe, M. G., Dukes, J. S., Langley, J. A., Ma, Z., Marïen, B., Reynaert, S., Ru, J., Song, J., Stocker, B., Terrer, C., Thoresen, J., Vanuytrecht, E., Wan, S., Yue, K., and Vicca, S.: When things get MESI: the Manipulation Experiments Synthesis Initiative – a coordinated effort to synthesize terrestrial global change experiments, Global Change Biology, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb. 16585, 2023.

• Marqués, L., Hufkens, K., Bigler, C., Crowther, T. W., Zohner, C. M., and Stocker, B. D.: Acclimation of phenology relieves leaf longevity constraints in deciduous forests, Nature Ecology & Evolution, pp. 1– 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01946-1, 2023.

• Bloomfield, K. J., Stocker, B. D., Keenan, T. F., and Prentice, I. C.: Environmental controls on the light use efficiency of terrestrial gross primary production, Global Change Biology, 29, 1037–1053, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16511, 2023.

2022

• Qiu, C., Ciais, P., Zhu, D., Guenet, B., Chang, J., Chaudhary, N., Kleinen, T., Li, X., Müller, J., Xi, Y., Zhang, W., Ballantyne, A., Brewer, S. C., Brovkin, V., Charman, D. J., Gustafson, A., Gallego-Sala, A. V., Gasser, T., Holden, J., Joos, F., Kwon, M. J., Lauerwald, R., Miller, P. A., Peng, S., Page, S., Smith, B., Stocker, B. D., Sannel, A. B. K., Salmon, E., Schurgers, G., Shurpali, N. J., Warlind, D., and Westermann, S.: A strong mitigation scenario maintains climate neutrality of northern peatlands, One Earth, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.12.008, 2022.

• Joshi, J., Stocker, B. D., Hofhansl, F., Zhou, S., Dieckmann, U., and Prentice, I. C.: Towards a unified theory of plant photosynthesis and hydraulics, Nature Plants, 8, 1304–1316, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-022-01244-5, 2022.

• Yu, X., Orth, R., Reichstein, M., Bahn, M., Klosterhalfen, A., Knohl, A., Koebsch, F., Migliavacca, M., Mund, M., Nelson, J. A., Stocker, B. D., Walther, S., and Bastos, A.: Contrasting drought legacy effects on gross primary productivity in a mixed versus pure beech forest, Biogeosciences, 19, 4315–4329, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-4315-2022, 2022.

• McCarthy, M., Meier, F., Fatichi, S., Stocker, B. D., Shaw, T. E., Miles, E., Dussaillant, I., and Pellicciotti, F.: Glacier contributions to river discharge during the current Chilean megadrought, Earth’s Future, n/a, e2022EF002 852, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF002852, 2022.

2021

• Favero, A., Mendelsohn, R., Sohngen, B., and Stocker, B.: Assessing the long-term interactions of climate change and timber markets on forest land and carbon storage, Environmental Research Letters, 16, 014 051, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abd589, 2021

• Ma, H., Mo, L., Crowther, T. W., Maynard, D. S., van den Hoogen, J., Stocker, B. D.,Terrer, C., and Zohner, C. M.: The global distribution and environmental driversof aboveground versus belowground plant biomass, Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5,1110–1122, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01485-1, 2021.

2020

• Joos, F., Spahni, R., Stocker, B. D., Lienert, S., Müller, J., Fischer, H., Schmitt, J., Prentice, I. C., Otto-Bliesner, B., and Liu, Z.: N2O changes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the preindustrial – Part 2: terrestrial N2O emissions and carbon– nitrogen cycle interactions, Biogeosciences, 17, 3511–3543, https://doi.org/10. 5194/bg-17-3511-2020, 2020.

• Stocker, B. D., Wang, H., Smith, N. G., Harrison, S. P., Keenan, T. F., Sandoval, D., Davis, T., and Prentice, I. C.: P-model v1.0: an optimality-based light use efficiency model for simulating ecosystem gross primary production, Geosci. Model Dev., 13, 1545–1581, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-1545-2020, 2020.

• Franklin, O., Cramer, W., Pietsch, S., Prentice, I.C.,Wang Han, Brännström, Å., Dieckmann, U.,Falster, D., Farrior, C., Hofhansl, F., Penuelas, J., Mäkelä, A., Manzoni, S., Rebel, K., Rovenskaya, E., Soudzilovskaia, N., Stocker, B. D., Terrer, C., van Bodegom, P., Wright, I., Zaehle, S.: Organizing principles for vegetation dynamics, Nature Plants, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-020-0655-x, 2020.

• Peaucelle, M., Janssens, I. A., Stocker, B. D., Descals Ferrando, A., Fu, Y. H., Molowny-Horas, R., Ciais, P., and Peñuelas, J.: Spatial variance of spring phenology in temperate deciduous forests is constrained by background climatic conditions, Nature Communications, 10, 5388, https://doi.org/10. 1038/s41467-019-13365-1, 2019.

Published data and code

2025

• Stocker, B., Hufkens, K., Bernhard, F., Marqués, L., Arán, P., Maspons, J., Marcadella, M. and Kurth, A., and Peng, Y.: geco-bern/rsofun: rsofun 5.1.0, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17313273, 2025. [R package]

2024

• Bernhard, F., Hufkens, K., Stocker, B., and Gribi, P.: geco-bern/map2tidy: v2.1, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13356532, 2024. [R package]

• Stocker, B. D. and Tian, D.: geco-bern/leafnp_data: v1.0: Initial release, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11071944, 2024. [Dataset]

• Stocker, B. D. and Tian, D.: geco-bern/leafnp: v1.0: Initial release, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11071816, 2024 [Code]

• Stocker, B., Perkowski, E., and Peng, Y.: geco-bern/lt cn review: v2.1 Analysis code for Stocker et al., 2024 (New Phytologist) Empirical evidence and theoretical un- derstanding of ecosystem carbon and nitrogen cycle interactions, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13736727, 2024. [Code]

2023

• Peng, Y. and Stocker, B. D.: Yunke Peng et al. Journal of Ecology 2023, https://doi.org/DOI:10.5281/zenodo.10532099, 2024. [Dataset]

• Sundert, K. V., Leuzinger, S., Bader, M. K.-F., Chang, S. X., Kauwe, M. G. D., Dukes, J. S., Langley, J. A., Ma, Z., Marien, B., Reynaert, S., Ru, J., Song, J., Stocker, B. D., Terrer, C., Thoresen, J., Vanuytrecht, E., Wan, S., Yue, K., Geunens, O., Goeminne, G.-J., Torfs, J. R. R., Vrijens, D., and Vicca, S.: MESI: a database of terrestrial global change experiments, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10423853, 2023. [Dataset]

• Giardina, F.: fgiardin/fET: Accepted for publication, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8186408, 2023 [Code] • Marqués, L., Stocker, B., and Hufkens, K.: geco-bern/GFDY: v2.0, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8271848, 2023. [Codę]

2022

• Giardina, F., Gentine, P., Konings, A., and Stocker, B.: fET time series, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6885164, 2022. [Dataset]

• Stocker, B.: geco-bern/mct: v4.0, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7429129, 2022 [Code]

Marqués, L., Stocker, B., and Hufkens, K.: computationales/phenoEOS: v4.0 (v4.0), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7245870, 2022. [Code]

2021

• Benjamin Stocker, & Koen Hufkens. (2021). rpmodel v1.2.0: R package implementing the P-model (v1.2.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4773325 [R package] • R package rpmodel published also on CRAN • Stocker, B., Hufkens, K., and Bernhard, F.: geco-bern/cwd: v1.0: Initial release, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14249539, 2024 [R package]

• Benjamin Stocker, & Koen Hufkens. (2021). ingestr v1.3: R package for environmental data ingest (v1.3). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5531240 [R package]